Bridgestone researches sustainable tires

Bridgestone’s new Arizona R&D center studying promising alternative to traditional rubber

As the world painfully discovered with petroleum, it’s best to be diversified, both geographically and in terms of input. With both goals in mind, as well as a corporate aim to eventually source all of its tires from renewable, sustainable sources, Bridgestone Americas recently broke ground on a new Biorubber Process Research Center in Mesa, Ariz. The facility will allow Bridgestone officials to research the use of the local guayule (pronounced why-u-lee) plant as a new, homegrown source of rubber to build all types of tires and rubber products.

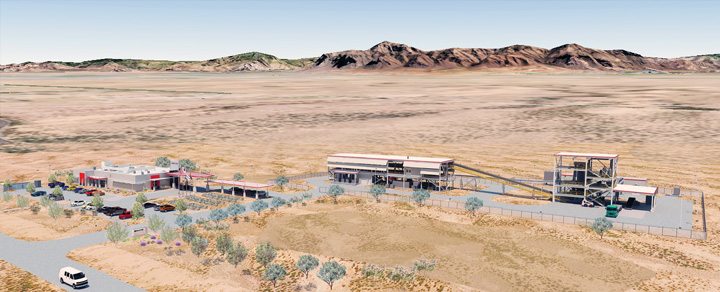

Once completed, Bridgestone’s new center will house 40 researchers and technicians on a 10-acre site, including an 8,400-square-foot laboratory, a four-platform shrub prep building and a 3,100-square-foot mechanical and electrical building. The team will examine all aspects — cultivation, tire production and finding profitable uses for the woody biomass that remains after the rubber has been extracted. It’s estimated the first rubber samples will be ready for tire evaluations sometime in 2015.

The vast majority of the world’s rubber supply currently comes from the Hevea brasiliensis tree, which is native to Latin America. That rubber source is almost entirely cultivated in far-flung places, however, like Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand. That distance from North America causes logistical and cost pressures that — combined with the accelerated development in those countries — has steadily driven up the price of rubber.

Cultivating hevea so far away from its native land also introduces the possibility that disease could sweep through the trees, causing a major price shock for consumers and tire manufacturers.

Once the rubber is extracted from the guayule plant, the end result used to make tires is absolutely identical in all aspects from those made with traditional rubber.

“We believe it’s essentially a direct replacement,” said Bill Niaura, director of new business development at Bridgestone Americas. “There probably are some advantages internally in the processing side, but in terms of performance, we get exactly the favorable qualities that traditional, natural rubber provides.”

Above it all is Bridgestone’s desire to provide a local, sustainable alternative to the traditional rubber tree, which is expected to become increasingly more expensive in the foreseeable future.

“It’s a commodity that we forecast will continue to increase in price. I benchmark it against petroleum, where there’s a price point where it makes sense to drill for oil in Texas, there’s a higher price point where it makes sense to build a drilling rig out into the Gulf … and there are higher price points where it makes sense to go to Canada and extract it from tar sands,” Niaura said.

Resurrecting an old idea

Using guayule to make rubber is an old idea that originated back in the early 1900s, with occasional stops and starts ever since, Niaura said. The Continental-Mexican Rubber Company and Intercontinental Rubber Company cultivated the plant in the Mexican desert for commercial purposes until blight wiped out much of the crop.

Guayule’s second chance came as part of the Emergency Rubber Project during World War II, which sought to ensure the production of rubber — a vital war material. This Department of Defense project unearthed much of the biological and agricultural knowledge that has fueled sporadic attempts at guayule production in the following decades.

While the military likely still has an interest in local sources of rubber, Bridgestone’s project is solely centered on commercial uses for the plant.

Because agricultural land is scarce and finite, part of the team’s challenge will be finding ways to integrate with the preexisting agribusiness structure in place throughout North America. That means making the crop feasible for Bridgestone, as well as the farmers that, ideally, would choose to cultivate it on their own.

“We’re not adding [additional] farmland, so it’s going to compete with something and our vision is that it competes with relatively low-value, non-food crops,” Niaura said.

Unlike corn-based ethanol, which contributed to corn price shocks that raised food scarcity concerns, Niaura expects guayule to primarily displace cotton production. And, as a water consumer, it uses much less water, which is a significant consideration in the perpetually water-starved desert southwest.

If the agricultural side is successful, and if a profitable use can be found for the remaining biomass once the rubber is extracted, Niaura expects guayule production to lead to greener tires that are less susceptible to price shocks and transportation costs, as well as stimulating job-growth in North America.

“I’m not going to make any grand promises,” he said. “But you could say that if everything works out, we may have a new domestic industry here.”