Profit. And cash.

Your CPA is sitting across the desk from you. She just told you that you had a good year. You did $5 million in sales, and had a bottom line of $200,000. “That’s a 4 percent net profit,” she says, sitting back, waiting for your reaction.

And what was it you said? Do you remember? I do. You said: “If I made $200,000, THEN WHERE IS IT?”

You are not the only owner this January who has said the very same thing. OK, change the numbers, but across this whole country, CPAs and bookkeepers are hearing the same thing: “Where is it?”

You are all good at making money, but some of you have no idea where that money is when the buzzer sounds. There are three kinds of people: People who make things happen; people that things happen to; and people who wonder “What happened?” You don’t want to be in that third category. So what happened?

Profit comes to us first as cash or receivable but it quickly migrates to other assets as we buy inventory, equipment and goodies (think of that huge new fish tank you put in the entry). And, any time an asset increases in size it has used up your cash. That fish tank is not an expense. It did not affect profit. But it still moved cash out of your bank account.

Not only assets, but liabilities can also suck up cash. Anytime a liability is paid down, that is a use of your cash.

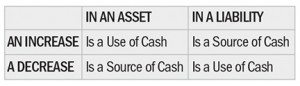

When an assets goes up, it is a use of cash. When a liability goes down, that also is a use of cash.

And the converse is true. If you decrease an asset by selling it, that is a source of cash. And, if you increase a liability (borrow more money at the bank), that is a source of cash. All of this can be represented in the following simple diagram:

Are you starting to think about where your $200,000 is? Looking at that fish tank? Thinking about that new shop truck? Remembering that balloon payment you made on the mortgage?

All of this action takes place on the balance sheet. It doesn’t have a thing to do with expenses. Expenses were all subtracted from gross margin, and reported above the profit/loss line. Nope. This is just the movement of cash between assets and liabilities (and equity, but that is another story). This movement of money can suck up every penny of profit you made without you even being aware of it. No controls on buying stuff or paying bills, and you are suddenly out of cash. Duh.

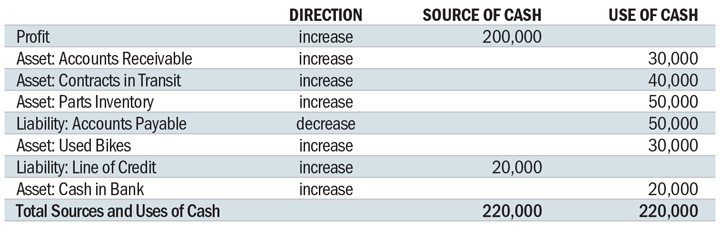

Let’s talk about that $200,000 that Mrs. CPA is telling you about. She does a little work, produces what she calls a Statement of Sources and Uses of Funds, and shows you that:

For the year, you had $200,000 in profit from operations. That is a source of cash. But:

• You also let your Accounts Receivable rise over the year from an average of $50,000 up to $80,000. That used up $30,000 of your cash.

• Your contracts in transit rose by $40,000. Another use of your cash.

• Parts inventory went from $200,000 to $250,000. That’s $50,000 more in cash tied up.

• Accounts Payable was $300,000 in January. At the end of December it was down to $250,000. You used $50,000 to lower it.

• Used bikes were $80,000 at the start of the year. They are now up to $110,000. That’s $30,000 more in cash now locked up until you sell them off.

• The line of credit rose from $50,000 up to $70,000 at year-end. That was a source of cash by borrowing the $20,000.

The score? (Notice here that your cash in bank is listed as a “use of funds.” Like all assets, if it goes up, that is how you used the money. You put in in the bank. When you take it out, it becomes a source.) So, with your $200,000 in profit you show only a $20,000 increase in cash. And you got that only by borrowing it against your line of credit. Bummer. But now you know what happened. You know where cash went, where cash came from, and the net effect.

My great-uncle Pete Ethington employed about 200 Casa Grande cotton-pickers in 1930s Arizona. Payday for them was every Friday afternoon. My Dad could remember being in Uncle Pete’s office on Friday morning, and watching him work the phones: Selling corn, hay, beans, cotton, flax, whatever else he had to make payroll. He never heard of a Cash Flow Statement. But he understood where his money went, and how to turn it back to cash when he had to have it.

Uncle Pete died with millions. And he did it in times that were much harder than we deal with today. He did it. And so can you. Keep smiling. This is fun, remember? (P.S. Lose the fish tank.)

Hal Ethington has been associated with the powersports industry for more than 40 years. Ethington is a senior analyst at ADP Lightspeed. Contact him at Hal.Ethington@adp.com.